Notes on Diffusion Models (I) -- DDPM and DDIM

Published on September 1, 2025

Introduction

A central challenge in machine learning, particularly in generative modeling, is to model complex datasets using highly flexible families of probability distributions that maintain analytical or computational tractability for learning, sampling, inference, and evaluation.

This post summarizes the fundamental concepts of diffusion models, their optimization strategies, and applications, focusing on the mathematical foundations and practical implications.

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM)

Diffusion models are a class of generative models first proposed by [1]. Inspired by nonequilibrium thermodynamics, the method systematically and gradually destroys data structure through a forward diffusion process, then learns a reverse process to restore structure and yield a highly flexible and tractable generative model.

Forward Process

A diffusion model formulates the learned data distribution as \(p_\theta(x_0) := \int p_\theta(x_{0:T})dx_{1:T}\), where \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_T\) are latent variables with the same dimensionality as the real data \(x_0 \sim q(x_0)\).

The forward process is a Markov chain where transitions from \(x_t\) to \(x_{t+1}\) follow multivariate Gaussian distributions. The joint distribution of latent variables (\(x_{1:T}\)) given the real data \(x_0\) is:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:diff_model_origin} q\left(\mathbf{x}_{1: T} \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right):=\prod_{t=1}^T q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\right), \quad q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\right):=\mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}_t ; \sqrt{1-\beta_t} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}, \beta_t \mathbf{I}\right). \end{equation}\]Key properties:

- The coefficients \(\{\beta_t\}\) are pre-defined and determine the “velocity” of diffusion.

- After sufficient diffusion steps, the final state \(x_T\) approaches an isotropic Gaussian distribution when \(T\) is large enough.

- For clarity, we use \(p_\theta\) to represent the learned distribution and \(q\) to represent the real data distribution.

A notable property of this forward process, as mentioned in [2] (Section 2), is that \(x_t\) has a closed-form expression derived using the reparameterization trick. Let \(\alpha_t = 1-\beta_t\) and \(\bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{i=1}^t\alpha_i\):

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{x}_t=&\sqrt{\alpha_t}\mathbf{x}_{t-1}+\sqrt{1-\alpha_t}\mathbf{\epsilon}_{t-1}\nonumber\\ =&\sqrt{\alpha_t}(\sqrt{\alpha_{t-1}}\mathbf{x}_{t-2}+\sqrt{1-\alpha_{t-1}}\mathbf{\epsilon}_{t-2})+\sqrt{1-\alpha_t}\mathbf{\epsilon}_{t-1}\nonumber\\ =&\sqrt{\alpha_t\alpha_{t-1}}\mathbf{x}_{t-2}+\left(\sqrt{\alpha_t(1-\alpha_{t-1})}\mathbf{\epsilon}_{t-2}+\sqrt{1-\alpha_t}\mathbf{\epsilon}_{t-1}\right)\nonumber\\ =&\sqrt{\alpha_t\alpha_{t-1}}\mathbf{x}_{t-2}+\sqrt{1-\alpha_t\alpha_{t-1}}\bar{\epsilon}_{t-2},~~~~~~\bar{\epsilon}_{t-2}\sim\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0,I})(*)\nonumber\\ =&\cdots\nonumber\\ =&\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}\mathbf{x}_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\bar{\epsilon},~~~~~~\bar{\epsilon}\sim\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0,I})\label{eq:xt_x0_relation} \end{align}\]\(^*\) The sum of two uncorrelated multivariate normal distributions \(\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_1,\sigma_1^2\mathbf{I})\) and \(\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_2,\sigma_2^2\mathbf{I})\) is also a multivariate normal distribution \(\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_1 + \boldsymbol{\mu}_2,(\sigma_1^2+\sigma_2^2)\mathbf{I})\) (proof details).

Typically, we can afford larger update steps when the sample becomes noisier, so \(\beta_1 < \beta_2 < \cdots < \beta_T\) and therefore \(\bar{\alpha}_1 > \bar{\alpha}_2 > \cdots > \bar{\alpha}_T\).

Reverse Process

Ideally, if we knew \(q(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t)\), we could gradually remove noise from corrupted samples to recover the original image. However, this conditional distribution is not readily available and its computation requires the entire dataset. Specifically:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:imprac_cond_prob_expr} q(\mathbf{x}_{t-1}|\mathbf{x}_t)=\frac{q(\mathbf{x}_{t-1},\mathbf{x}_t)}{q(\mathbf{x}_t)}=q(\mathbf{x}_t|\mathbf{x}_{t-1})\frac{q(\mathbf{x}_{t-1})}{q(\mathbf{x}_t)}=q(\mathbf{x}_t|\mathbf{x}_{t-1})\frac{\int_{\mathbf{x}_0}q(\mathbf{x}_{t-1}|\mathbf{x}_0)\text{d}\mathbf{x}_0}{\int_{\mathbf{x}_0}q(\mathbf{x}_t|\mathbf{x}_0)\text{d}\mathbf{x}_0}. \end{equation}\]Computing \(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) requires evaluating integrals in Eq. (\ref{eq:imprac_cond_prob_expr}), which is computationally expensive. Instead, we use the diffusion model \(p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) to learn and approximate the true conditional distribution. When \(\beta_t\) is sufficiently small, \(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) is also Gaussian (details).

The joint distribution of the diffusion model is:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:dm_joint_dist} p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{0: T}\right)=p\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right) \prod_{t=1}^T p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right) \quad p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} ; \boldsymbol{\mu}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right), \mathbf{\Sigma}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)\right). \end{equation}\]With this distribution, we can sample from an isotropic Gaussian distribution and expect the reverse process to gradually transform it into samples that follow \(p_\theta(x_0) \approx q(x_0)\).

Loss Function

The loss function for training the diffusion model is the standard variational bound on negative log likelihood:

\[\begin{align*} \log p_\theta(x_0) =& \log\int_{x_{1:T}}p(x_{0:T})\mathrm{d}x_{1:T} \\ =& \log\int_{x_{1:T}}p(x_{0:T})\frac{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\mathrm{d}x_{1:T} \\ =& \log\mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\left[\frac{p(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\right]\\ \geq&\mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\left(\log\left[\frac{p(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\right]\right). \end{align*}\]Therefore, the expected negative log likelihood is lower bounded by the variational lower bound:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbb{E}_{q(x_0)}\left[-\log p_\theta(x_0)\right] \geq & \mathbb{E}_{q(x_0)}\left[-\mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\left(\log\left[\frac{p(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\right]\right)\right] \\ =& -\mathbb{E}_{q(x_{0:T})}\left(\log\left[\frac{p(x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T}|x_0)}\right]\right)\\ =&: L_\text{VLB}. \end{align*}\]To convert each term in the equation to be analytically computable, the objective can be further rewritten to be a combination of several KL-divergence and entropy terms (See the detailed step-by-step process in Appendix B in [1]):

\[\begin{aligned} L_{\mathrm{VLB}} & =\mathbb{E}_{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{0: T}\right)}\left[\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{1: T} \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{0: T}\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[\log \frac{\prod_{t=1}^T q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right) \prod_{t=1}^T p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)+\sum_{t=1}^T \log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)+\sum_{t=2}^T \log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)}+\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_1 \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)+\sum_{t=2}^T \log \left(\frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)} \cdot \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}\right)+\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_1 \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)+\sum_{t=2}^T \log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)}+\sum_{t=2}^T \log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}+\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_1 \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)+\sum_{t=2}^T \log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)}+\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_T \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{q\left(\mathbf{x}_1 \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}+\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_1 \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right)}\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q\left[\log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_T \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)}+\sum_{t=2}^T \log \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)}-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right)\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_q[\underbrace{D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathbf{x}_T \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)\right)}_{L_T}+\sum_{t=2}^T \underbrace{D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)\right)}_{L_{t-1}} \underbrace{-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right)}_{L_0}]. \end{aligned}\]In summary, we can split the variational lower bound into \((T+1)\) components and label them as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} L_{\mathrm{VLB}} & =L_T+L_{T-1}+\cdots+L_0 \\ \text { where } L_T & =D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathbf{x}_T \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_T\right)\right), \\ L_t & =D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}, \mathbf{x}_0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}\right)\right) \text { for } 1 \leq t \leq T-1, \\ L_0 & =-\log p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_1\right). \end{aligned}\]In the above decomposition:

- \(q(x_T \mid x_0)\) can be computed from Eq. (\ref{eq:xt_x0_relation})

- \(p_\theta(x_t \mid x_{t+1})\) are parameterized and learned

Next, we show that \(q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}, \mathbf{x}_0 \right)\) can be computed in closed form even though \(q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1} \right)\) can’t.

\[\begin{align} q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right) & =q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1}, \mathbf{x}_0\right) \frac{q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}{q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_0\right)}\nonumber \\ & \propto \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\left(\mathbf{x}_t-\sqrt{\alpha_t} \mathbf{x}_{t-1}\right)^2}{\beta_t}+\frac{\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1}-\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \mathbf{x}_0\right)^2}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}-\frac{\left(\mathbf{x}_t-\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0\right)^2}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\right)\right)\nonumber \\ & =\exp \left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\mathbf{x}_t^2-2 \sqrt{\alpha_t} \mathbf{x}_t \mathbf{x}_{t-1}+\alpha_t \mathbf{x}_{t-1}^2}{\beta_t}+\frac{\mathbf{x}_{t-1}^2-2 \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \mathbf{x}_0 \mathbf{x}_{t-1}+\bar{\alpha}_{t-1} \mathbf{x}_0^2}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}-\frac{\left(\mathbf{x}_t-\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0\right)^2}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\right)\right)\nonumber \\ & =\exp \left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\left(\frac{\alpha_t}{\beta_t}+\frac{1}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}\right) \mathbf{x}_{t-1}^2-\left(\frac{2 \sqrt{\alpha_t}}{\beta_t} \mathbf{x}_t+\frac{2 \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \mathbf{x}_0\right) \mathbf{x}_{t-1}+C\left(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)\right)\right) \ \end{align}\]From the above derivation, we observe that the conditional distribution \(q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)\) is also Gaussian and can be written in standard multivariate normal form as \(q\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(x_{t-1};\tilde{\mu}(x_t,x_0), \tilde{\beta}_t\mathbf{I}\right)\). Notice that \(ax^2+bx+c =\frac{1}{1/a}\left(x^2+\frac{b}{a}x+\frac{c}{a}\right)=\frac{1}{1/a}\left((x+\frac{b}{2a})^2+\text{ const }\right)\), the \(\tilde{\mu}\) and \(\tilde{\beta}_t\) can be computed as follows,

\[\begin{align} \tilde{\beta}_t &= 1/\left(\frac{\alpha_t}{\beta_t}+\frac{1}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}\right)=\frac{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\beta_t\label{eq:standard_form_beta_t},\\ \tilde{\mu}(x_t,x_0) &= \left(\frac{\sqrt{\alpha_t}}{\beta_t} \mathbf{x}_t+\frac{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \mathbf{x}_0\right) /\left(\frac{\alpha_t}{\beta_t}+\frac{1}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}\right)\nonumber\\ &= \frac{\sqrt{\alpha_t}\left(1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}\right)}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_t+\frac{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \beta_t}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0\label{eq:standard_form_mu_t}. \end{align}\]Recall the relation between \(x_t\) and \(x_0\) deduced from Eq. \ref{eq:xt_x0_relation}, the Eq. \ref{eq:standard_form_mu_t} can be further rewrited as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}_t & =\frac{\sqrt{\alpha_t}\left(1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}\right)}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_t+\frac{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \beta_t}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}}\left(\mathbf{x}_t-\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \epsilon_t\right) \\ & =\frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha_t}}\left(\mathrm{x}_t-\frac{1-\alpha_t}{\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}} \epsilon_t\right) \end{aligned}\]Parameterization of reverse diffusion process and \(L_t\)

Recall our previous decomposition of variational lower bound loss, we have closed form computation of real data distribution (i.e. \(q(x_T\mid x_0)\) and \(q(x_t\mid x_{t+1}, x_0)\)), we still need a parameterization of \(p_\theta(x_t\mid x_{t+1})\). As we discussed previously, when \(\beta_t\) is small enough, we can approximate \(q(x_t\mid x_{t+1})\) by the Gaussian distribution \(p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} ; \boldsymbol{\mu}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right), \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)\right)\). We expect that the training process can let \(\mu_\theta\) to predict \(\tilde{\mu}_t\). With this parameterization, each component of loss function \(L_t=D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}, \mathbf{x}_0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}\right)\right)\) is the KL divergence between two multivariate Gaussian distributions and has a relatively simple closed form. The loss term \(L_t\) become

\[\begin{align} L_t =& D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}, \mathbf{x}_0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t+1}\right)\right)$ \nonumber\\ =& \frac{1}{2}\left[\log\frac{| \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)|}{|\tilde{\beta}_t \mathbf{I}|}+(\tilde{\mu}_t-\mu_\theta)^T\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)^{-1}(\tilde{\mu}_t-\mu_\theta)+\text{tr}\left\{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)^{-1}\tilde{\beta}_t \mathbf{I}\right\}\right].\label{eq:lt_before_simple_sigma} \end{align}\]In practice, we can further simplify the loss function Eq. (\ref{eq:lt_before_simple_sigma}) by predefine the variancen matrix as \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)=\sigma_t^2\mathbf{I}\) and, experimentally, \(\sigma_t^2=\tilde{\beta}_t=\frac{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}{1-\bar{\alpha_t}}\beta_t\) or \(\sigma^2_t=\beta_t\) had similar results. Therefore, we can write:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:lt_mu_t_not_param} L_{t-1}=\mathbb{E}_q\left[\frac{1}{2 \sigma_t^2}\left\|\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}_t\left(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0\right)-\boldsymbol{\mu}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)\right\|^2\right]+C. \end{equation}\]Furthermore, \(\mu_\theta\) is further parameterized in section 3.2 of [2] to be corresponded with the form of \(\tilde{\mu}_t\) in Eq. (\ref{eq:standard_form_mu_t}) as follows,

\[\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\mu}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)=\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}_t\left(\mathbf{x}_t, \frac{1}{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}}\left(\mathbf{x}_t-\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \epsilon_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t\right)\right)\right)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha_t}}\left(\mathbf{x}_t-\frac{\beta_t}{\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)\right). \end{equation}\]In this parameterization, the neural network will be used to approximate the \(\epsilon_\theta\) instead of \(\mu_\theta\) directly. This parameterization further simplify \(L_{t-1}\) in Eq. (\ref{eq:lt_mu_t_not_param}) into

\[\begin{equation} L_{t-1} = \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_0, \boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\left[\frac{\beta_t^2}{2 \sigma_t^2 \alpha_t\left(1-\bar{\alpha}_t\right)}\left\|\boldsymbol{\epsilon}-\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_\theta\left(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}, t\right)\right\|^2\right]. \end{equation}\]To this point, every term in \(L_\text{VLB}\) can be computed in explicit closed form and is ready for training. However, empirically, [2] found that training the diffusion model works better with a simplified objective that ignores the weighting term:

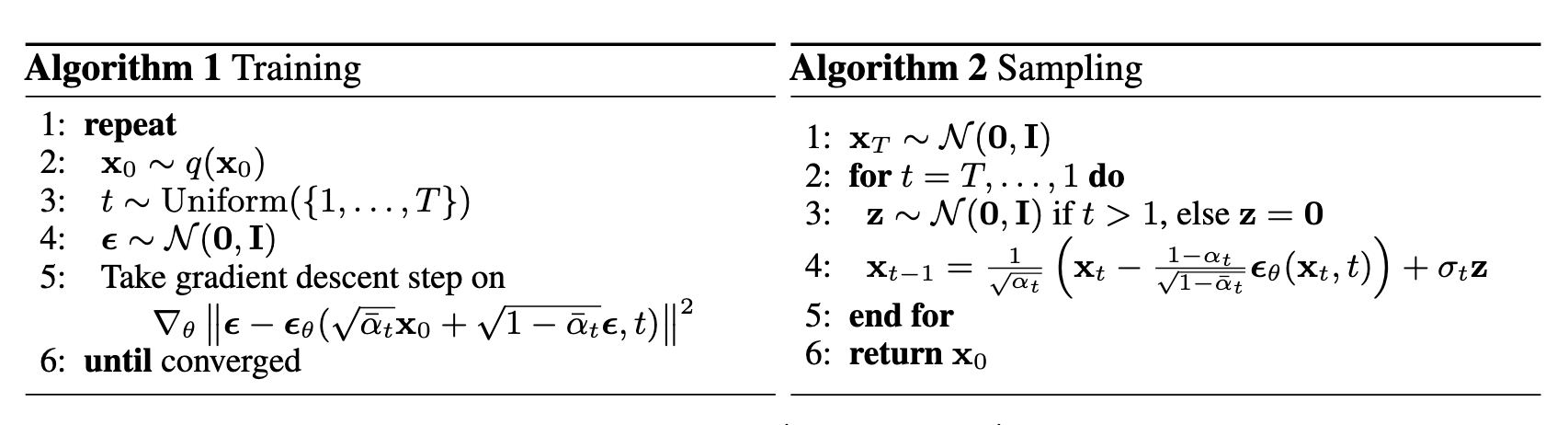

\[\begin{aligned} L_t^{\text {simple }} & =\mathbb{E}_{t \sim[1, T], \mathbf{x}_0, \epsilon_t}\left[\left\|\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_t-\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_\theta\left(\mathbf{x}_t, t\right)\right\|^2\right] \\ & =\mathbb{E}_{t \sim[1, T], \mathbf{x}_0, \epsilon_t}\left[\left\|\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_t-\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_\theta\left(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_t, t\right)\right\|^2\right] \end{aligned}\]This simplification enable us to compute arbitrary time steps for each sample \(x_0\), instead of computing the entire series as in \(L_\text{VLB}\). The entire DDPM algorithm is show as follows.

Side notes: The timestep is also an input to the neural network \(\epsilon_\theta(x_t, t)\) and it is typically encoded into some vector. For instance, in DDPM, integer timesteps are encoded into floats vector through sinusoidal function.

Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM)

Though diffusion models like DDPM [2] already demonstrated the ability to produce high quality samples that are comparable with the state-of-the-art generative model, such as GANs, the computation complexity of the sampling process is a critical drawback. These diffusion-based models typically require many iterations to produce a high quality sample, whereas models like GANs only need one iteration. A quantitative experiment in [3] shows that, with same GPU setup and similar neural network complexity, it takes around 20 hours to sample 50k images of size \(32\times 32\) from a DDPM, but less than a minute to do so from a GAN model. To resolve this high computational cost without lossing too much generation quality, [3] proposed Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models(DDIM). This algorithm is based on two observation/intuitives [4].

-

The deduction of the loss function only depends on \(q(x_t\mid x_0)\) and the sampling process only depends on \(p_\theta(x_{t-1}\mid x_t)\). To be more specific, the loss function remains the same form as long as the relation in Eq. (\ref{eq:xt_x0_relation}) still hold.

-

A DDPM trained on \(\{\alpha_t\}_{t=1}^N\) has, in fact, included the “knowledge” for training a DDPM with \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\subset\{\alpha_t\}_{t=1}^N\). This can be naturally observed from training process of the simplified version of loss function. It gives us a intuition that we can use a subset of parameters during the sampling process and reduce the computational cost.

Based on the first observation, we can build different conditional distributions \(q(x_t \mid x_{t+1}, x_0)\) that has the same \(q(x_t\mid x_0)\) distribution. Same marginal distribution \(q(x_t\mid x_0)\) results in the same loss function and different choices of conditional distribution \(q(x_t \mid x_{t+1}, x_0)\) results in different sampling choices. In fact, without the constraint of \(q(x_{t+1}\mid x_t)\) as in Eq. (\ref{eq:diff_model_origin}), we have a broader choice(i.e. a larger solution space) of \(q(x_t \mid x_{t+1}, x_0)\).

Based on the second observation, the sampling process can only use a subset of steps used in training process. By reducing the updating steps, the sampling process can greatly speed-up.

Non-Markovian Forward Processes

The key observation here is that the DDPM loss function only deppends on the marginals \(q(x_t\mid x_0)\), but not directly on the joint distribution \(q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)\) or transition distribution \(q(x_t\mid x_{t-1})\). Follow the deduction in [4], we can use undetermined coefficient method to compute the form of \(q(x_t\mid x_{t+1}, x_0)\) and we also assume it takes a normal distribution. We first summarize the condition as follows:

-

To maintain the same loss function, we need the same marginal distribution \(q(x_t\mid x_0)=\mathcal{N}(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}x_0, (1-\bar{\alpha}_t)\mathbf{I})\). The corresponded sampling process formula is \(x_t=\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_2}x_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\epsilon_1\).

-

Assume \(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)=\mathcal{N}(x_{t-1}; k_t x_t+\lambda_t x_0, \sigma^2\mathbf{I})\), where \(k_t\) and \(\lambda_t\) are coefficient to be decided. The sampling process with \(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)\) is \(x_{t-1} = k_t x_t+\lambda_t x_0 + \sigma_t\epsilon_2\).

By combining the marginal distribution \(q(x_t\mid x_0)\) and assumed form of \(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)\), we can compute the marginal distribution of \(x_{t-1}\) as follows,

\[\begin{align} x_{t-1} =& k_t x_t + \lambda_t x_0 + \sigma_t \epsilon_2\nonumber\\ =& k_t(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}x_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\epsilon_1) + \lambda_t x_0 + \sigma_t \epsilon_2\nonumber \\ =& (k_t\sqrt{\bar{\alpha_t}}+\lambda_t)x_0 + (k_t\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\epsilon_1+\sigma_t\epsilon_2)\nonumber\\ =& (k_t\sqrt{\bar{\alpha_t}}+\lambda_t)x_0 + \sqrt{k_t^2(1-\bar{\alpha}_t)+\sigma_t^2}\epsilon.\label{eq:sample_with_undeter_coefs} \end{align}\]Comparing Eq. (\ref{eq:sample_with_undeter_coefs}) with Eq. (\ref{eq:xt_x0_relation}), remember that we need to let the marginal distribution to be the same and \(q(x_{t-1}\mid x_0)=\int_{x_t}q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t, x_0)q(x_t\mid x_0)\mathrm{d}x_t\), we can have the following relation,

\[\begin{align} \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} &= k_t\sqrt{\bar{\alpha_t}}+\lambda_t,\nonumber\\ \sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} &= \sqrt{k_t^2(1-\bar{\alpha}_t)+\sigma_t^2}.\nonumber\\ \end{align}\]There are three variables and only two equation, therefore, we can view \(\sigma_t^2\) as a independent variable and solve that

\[\begin{align} k_t=&\sqrt{\frac{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}-\sigma^2_t}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t}}},\\ \lambda_t=&\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} - \sqrt{\frac{(1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}-\sigma^2_t)\alpha_t}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t}}}. \end{align}\]Therefore, we can obtain a family \(\mathcal{Q}\) of inference distribution indexed by \(\{\sigma_t\}_{1:T}\),

\[\begin{equation} q_\sigma\left(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_0\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \boldsymbol{x}_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}-\sigma_t^2} \cdot \frac{\boldsymbol{x}_t-\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{x}_0}{\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}}, \sigma_t^2 \boldsymbol{I}\right). \end{equation}\]As a result, in the sampling procedure, the updating formula is, \(\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}=\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \underbrace{\left(\frac{\boldsymbol{x}_t-\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \epsilon_\theta^{(t)}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t\right)}{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}}\right)}_{\text {"predicted } \boldsymbol{x}_0 \text { " }}+\underbrace{\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}-\sigma_t^2} \cdot \epsilon_\theta^{(t)}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t\right)}_{\text {"direction pointing to } \boldsymbol{x}_t \text { " }}+\underbrace{\sigma_t \epsilon_t}_{\text {random noise }}. \end{equation}\)

Comparing with DDPM, this is generalized form of generative processes. Since the marginal distribution remains the same, the loss function did not change and the training process is identical. This means that we can use this new generative process with a diffusion model trained in DDPM way and, with different level of \(\sigma_t\), we can generate different image with same initial noise. Among different choices, \(\sigma_t=0\) is a special case in which the generation process is deterministic given the initial noise. This model is called denoising diffusion implicit model since it is an implicit probabilistic model and it is trained with the DDPM objective.

Accelerate generation processes

We need to point out that, in our previous discussion, we did not start with \(q(x_t\mid x_{t-1})\) and the sequence \(\{\alpha_t\}\) determined the model. The key observation here is that the training process of DDPM, in its essence, contained the data/processes of training over any subsequence \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\subset\{\alpha_t\}\). This can be observed from the loss functions. The training process over a set of parameter \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\) is

\[\begin{equation} L_{\text {simple }}(\theta):=\mathbb{E}_{\tau, \mathbf{x}_0, \boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\left[\left\|\boldsymbol{\epsilon}-\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_\theta\left(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_\tau} \mathbf{x}_0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_\tau} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}, \tau\right)\right\|^2\right]. \end{equation}\]Therefore, DDPM trained on \(\{\alpha_t\}\) already incorporated information used to train DDPM on \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\subset\{\alpha_t\}\). When the size of \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\) is much smaller than \(\{\alpha_t\}\), generating samples with the former parameters set will be much faster.

Remarks on DDIM

- Why don’t we just directly train on \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\) and sample from the model?

There might be two considerations for training on T steps but sampling in \(\mathrm{dim}(\tau)\) steps. Firstly, diffusion model trained on more sophisticated setup might improve the model’s capability of generalization. Secondly, use subsequence to speed up is one way of acceleration and there might be other acceleration method with this more sophisticate model. - Can we use DDPM and sample with subset of parameters \(\{\alpha_\tau\}\)? What is the purpose of choosing this new family of conditional distribution?

For purpose of accelerating sample generation process, one can certainly use DDPM and skip some steps during generation [5]. However, clearly, the newly proposed distribution family is more flexible and has the potential of generate more diversified samples without any additional cost other than DDPM. As a matter of fact, letting \(\sigma_t^2 = \sqrt{\frac{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t}}}\beta_t\), the DDIM is equivalent to DDPM’s sampling process. - Additional benefit comes with DDIM?

DDIM has “consistency” property since the generative process is deterministic. It means that multiple samples conditioned on the same latent variable should have similar hig-level features [5]. Due to this consistency, DDIM can do semantically meaningful interpolation in the latent variable.

Result comparison between DDPM and DDIM

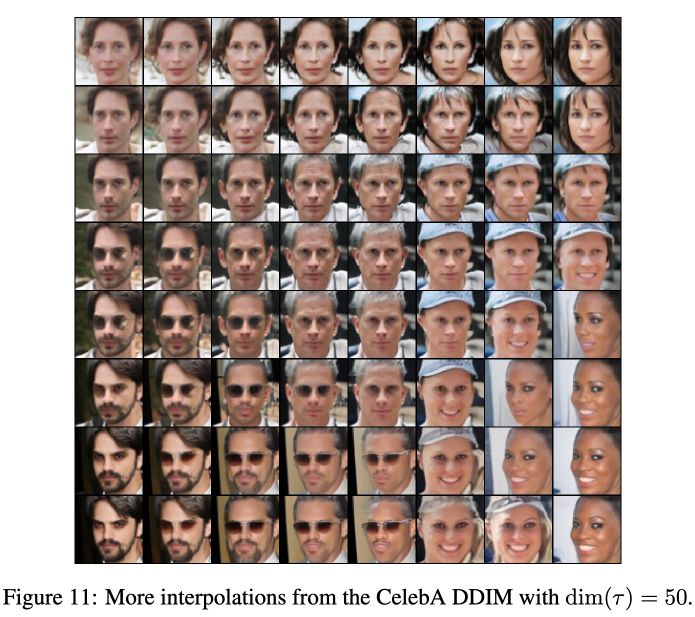

Experiments in DDPM and DDIM paper have quantitatively and qualitatively examined the images generated. Here we review two aspects: the sampling quality and the interpolation result.

Sampling quality

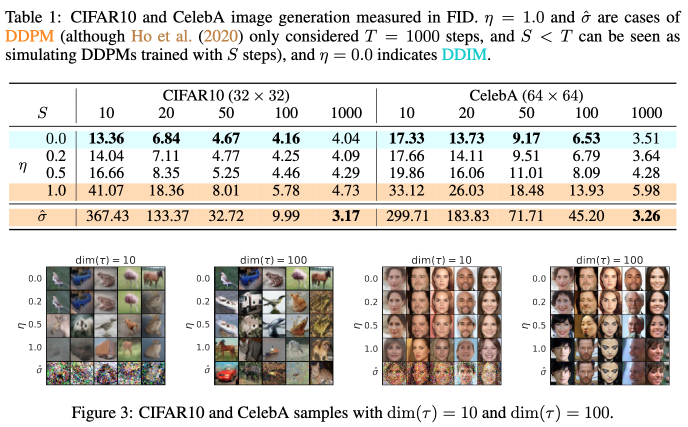

In DDIM’s experiment, as the following screenshot taken from it shows, the authors compared results of different number of diffusion steps \(\text{dim}(\tau)\) and different level of noise. The empirical result is that lower noise level \(\sigma_t^2\), the better image quality generated with accelerated diffusion process.

Interpolation

Both DDIM and DDPM examined their performance on interpolation of images. They use the forward process as stochastic encoder to generate embeddings \(x_0\rightarrow x_T, x'_0\rightarrow x'_T\). Then decoding the interploated latent \(\bar{x}_T=f(x_T, x'_T, \alpha)\) where \(\alpha\) represent interpolation parameter(s).

- In DDPM, the authors simply use a linear interpolation, i.e. \(\bar{x}_T=\alpha x_T + (1-\alpha)x'_T\).

- n DDIM, the authors use a spherical linear interpolation,

\(\boldsymbol{x}_T^{(\alpha)}=\frac{\sin ((1-\alpha) \theta)}{\sin (\theta)} \boldsymbol{x}_T+\frac{\sin (\alpha \theta)}{\sin (\theta)} \boldsymbol{x}_T',\) where \(\theta=\mathrm{arccos}\left(\frac{(\boldsymbol{x}_T)^T\boldsymbol{x}'_T}{\|\boldsymbol{x}_T\|\|\boldsymbol{x}_T'\|}\right)\).

Interesting Reading

References

- [1]J. Sohl-Dickstein, E. Weiss, N. Maheswaranathan, and S. Ganguli, “Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics,” in International Conference on Machine Learning, 2015, pp. 2256–2265. Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1503.03585.pdf

- [2]J. Ho, A. Jain, and P. Abbeel, “Denoising diffusion probabilistic models,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, pp. 6840–6851, 2020.

- [3]J. Song, C. Meng, and S. Ermon, “Denoising diffusion implicit models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02502, 2020.

- [4]苏剑林, “生成扩散模型漫谈(四):DDIM = 高观点DDPM.” July 2022. Available at: \urlhttps://kexue.fm/archives/9181

- [5]L. Weng, “What are diffusion models?,” lilianweng.github.io, Jul. 2021, Available at: https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2021-07-11-diffusion-models/